To call someone a manipulator is to criticize that person's character. To say that you have been manipulated is to complain of mistreatment. Manipulation is cunning at best and downright immoral at worst. But why is this? What's wrong with manipulation? People influence each other all the time and in all possible ways. But what distinguishes manipulation from other influences and what makes it immoral?

We are constantly being manipulated. Here are some examples. There is "gaslighting" which involves encouraging someone to question their own judgment and instead rely on the manipulator's advice. Guilt trips make a person feel overly guilty for not being able to do what the manipulator wants them to do. Charm and peer pressure make someone care so much about the approval of the manipulator that they will do what the manipulator wants.

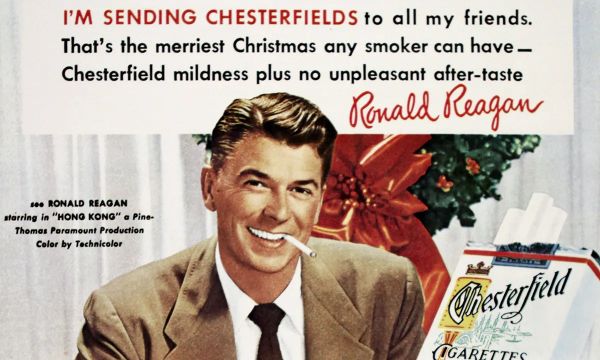

Advertising is manipulative when it encourages the audience to form false beliefs, such as when we are told that fried chicken is a healthy food, or false associations, as when Marlboro cigarettes are associated with the harsh energy of the Marlboro man. Phishing and other scams manipulate their victims through a combination of deceit (from outright lies to fake phone numbers or URLs) and playing on emotions such as greed, fear, or empathy. Then there is more direct manipulation, perhaps the most famous example of which is when Iago manipulates Othello to create suspicion of Desdemona's loyalty, playing on his insecurities to make him jealous and driving him into a rage that causes Othello to kill his beloved. All of these examples of manipulation share a sense of immorality. What do they have in common?

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it harms the person being manipulated. Of course, manipulation often hurts. If successful, manipulative cigarette advertising promotes disease and death; manipulative phishing and other types of fraud facilitate identity theft and other forms of fraud; manipulative social tactics can support abusive or unhealthy relationships; political manipulation can provoke division and weaken democracy. But manipulation is not always harmful.

Suppose Amy has just left an abusive but loyal partner, but in a moment of weakness she is tempted to return to him. Now imagine that Amy's friends use the same tricks that Iago used in Othello. They manipulate Amy into (falsely) believing—and outraged—that her ex-partner was not only abusive, but also unfaithful. If this manipulation prevents Amy from reconciling, she may be better off than if her friends hadn't manipulated her. However, this may still seem morally quirky to many. Intuitively, it would be morally better for her friends to use non-manipulative means to help Amy avoid defection. Something remains morally questionable about manipulation, even when it helps rather than harms the person being manipulated. So harm cannot be the reason that manipulation is wrong.

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it involves methods that are inherently immoral ways of treating other people. This thought may be especially attractive to those who are inspired by Immanuel Kant's idea that morality requires us to treat each other as rational beings and not as mere objects. Perhaps the only correct way to influence the behavior of other sentient beings is through rational persuasion, and thus any form of influence other than rational persuasion is morally unacceptable. But for all its appeal, this answer is also untrue, as it would denounce many forms of influence that are morally favorable.

For example, much of Iago's manipulation involves appealing to Othello's emotions. But emotional appeals are not always manipulative. Moral persuasion often appeals to empathy or tries to convey what it feels like when others do to you what you do to them. Likewise, making someone feel fearful of something that is truly dangerous, feel guilty about something that is truly immoral, or feel a reasonable level of confidence in their actual abilities is not like manipulation. Even an invitation to question one's own judgment may not be manipulative in situations where—perhaps due to intoxication or strong emotions—there really is a good reason for doing so. Not every form of irrational influence seems to be manipulative. Thus, it appears that whether influence is manipulative depends on how it is used. Iago's actions are manipulative and wrong because they are designed to make Othello think and feel the wrong things. Iago know

t that Othello has no reason to be jealous, but he still makes Othello jealous. This is the emotional counterpart to deception, which Iago also employs when he arranges things (such as a dropped handkerchief) to trick Othello into forming beliefs that Iago knows are false. Manipulative gaslighting occurs when a manipulator tricks another into distrusting what the manipulator considers sound judgment. In contrast, telling an angry friend to avoid snap judgments before cooling off is not a manipulative act if you know your friend's judgment is indeed temporarily unsound. When a scammer tries to get you sympathy for a non-existent Nigerian prince, he acts manipulatively because he knows it would be a mistake to feel sympathy for someone who does not exist. Yet a sincere call for sympathy for real people suffering from undeserved suffering is a moral persuasion, not a manipulation. When an abusive partner tries to make you feel guilty for suspecting him of the infidelity he just committed, he is acting manipulatively because he is trying to create misplaced guilt. But when a friend makes you feel enough guilt for leaving them in your time of need, it doesn't feel manipulative. Yet a sincere call for sympathy for real people suffering from undeserved suffering is a moral persuasion, not a manipulation. When an abusive partner tries to make you feel guilty for suspecting him of the infidelity he just committed, he is acting manipulatively because he is trying to create misplaced guilt. But when a friend makes you feel enough guilt for leaving them in your time of need, it doesn't feel manipulative. Yet a sincere call for sympathy for real people suffering from undeserved suffering is a moral persuasion, not a manipulation. When an abusive partner tries to make you feel guilty for suspecting him of the infidelity he just committed, he is acting manipulatively because he is trying to create misplaced guilt. But when a friend makes you feel enough guilt for leaving them in your time of need, it doesn't feel manipulative.

What makes an influence manipulative and what makes it wrong are the same thing: the manipulator is trying to get someone to accept what the manipulator himself considers to be an inappropriate belief, emotion, or other mental state. Thus, manipulation resembles a lie. What makes a statement false and what makes it morally wrong are the same thing: the speaker is trying to get someone to accept what the speaker himself says, regards as a false belief. In both cases, the goal is to get the other person to make some kind of mistake. The liar is trying to get you to accept a false belief. The manipulator may do this, but they may also try to make you feel an inappropriate (or inappropriately strong or weak) emotion, place too much weight on the wrong things (such as someone's approval), or question something (such as your own judgment or fidelity of your lover) that there is no good reason to doubt. The difference between manipulation and non-manipulative influence depends on whether the influencer is trying to get someone to make some mistake about what they think, feel, doubt, or pay attention to.

Inherent in the human condition is that we influence each other in all sorts of ways beyond mere rational persuasion. Sometimes these influences improve the other person's decision-making situation by making him believe, doubt, feel, or pay attention to the right things; sometimes they impair decision making by making her believe, doubt, feel, or pay attention to the wrong things. But manipulation involves the deliberate use of such influences to prevent a person from making the right decision—this is the immorality of manipulation.

This view of manipulation tells us something about how to recognize it. It is tempting to think that manipulation is a kind of influence. But, as we have seen, the types of influence that can be used to manipulate can also be used non-manipulatively. What matters in identifying manipulation is not what influence is used, but whether influence is used to put the other person in a better or worse position to make a decision. So, if we want to recognize manipulation, we must look not at the form of influence, but at the intention of the person using it. For it is the intention to worsen the decision-making situation of another person that is both the essence and the essential immorality of manipulation.