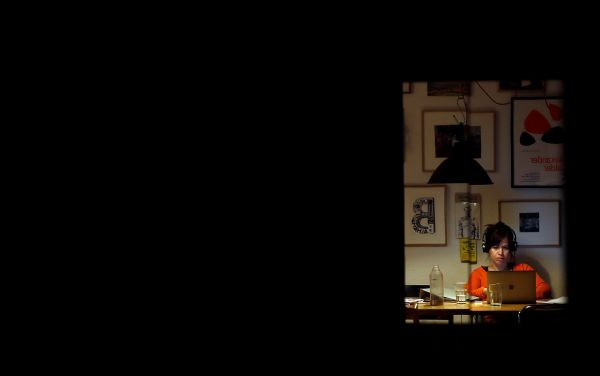

Adrienne Boyle, one of the most influential British flex activists of the last century, looked out the window of her houseboat in Dublin's historic Docklands. She had a good view of Google's 14-story European headquarters. “There’s not a lot of flexible work involved in this! The lights are on all night, 11:00 pm Saturday night,” she told me when I spoke to her in December 2017. "It's a flexible schedule, but you work 60 hours a week."

Long before the 2020 pandemic made remote work a necessity, employees at Anglo-American companies were saying they needed more flexibility about where and when they worked. A 2017 Gallup poll in the United States found that 51% of workers would be willing to change jobs to one that allows them some degree of control over their working hours, and 35% to one where the workplace is flexible. While flexibility was originally associated with women seeking to combine paid work with unpaid childcare, it has since become a key item on the list of desirable benefits for all workers. In the 21st century, the culture of flexible work has reached its apogee in large technology companies that have adopted concepts such as work-life balance, family friendliness and employee well-being as guiding principles.

However, even those employees who enjoy the benefits of flexibility—still a privileged minority—have found that this does not necessarily mean that their work lives have become easier or better. Flexibility can make it difficult to draw boundaries around paid employment and make it difficult to separate work from the rest of the day. Flexibility at work also did not solve the pressing problems of caring for children or the elderly, nor did it change the gender division of domestic work. While companies like Google and Facebook love to trumpet their employee benefits, they still haven't solved staff childcare issues and can't make their benefits available to everyone. The dramatic restructuring of the daily work lives of tens of millions of people due to the COVID-19 pandemic has also demonstrated how flexible work differs in different contexts:

The modern flexible work policy did not emerge in a moment of sudden crisis, but as a result of the slow burning of the second wave of feminist activism. In the 1970s, as more women entered the paid workforce, they continued to do a disproportionate share of childcare and housework. In awareness groups and campaigns that sprang up in the US and Europe, women became increasingly aware that what seemed "just" personal was in fact political. A new generation of activists pushed for a change in the structure and conditions of paid work. The idea was to make it more suitable for the needs of caregivers and allow women of all backgrounds to participate in the economy on an equal footing with men. Meanwhile, men will be urged to participate more fully in the upkeep of the home and family. Feminist activism for what we now call "flexibility" was part of the concept of rebuilding communities and supporting the needs of workers as human beings. This is most evident from the first-hand accounts of women who devoted their energy to reimagining paid work at a time when the 9-to-5 40-hour work week was a near-universal model of professional success.

In the decades since feminists first challenged the structures that regulate paid work, the vision behind their campaigns has been lost. While employers have embraced some feminist ideas about workplace reform, for the most part they have strategically bracketed the question of who ends up looking after the kids. Ironically, using feminist ideas to transform paid work has contributed more to a 24/7 work culture than it has opened up new opportunities for women. It is only by looking back at the earlier ideals that structured flexible employment policies that we can recover a fuller picture of what a vision of a future that would suit us all might mean. Born in 1946, Boyle is one of eight children in a working-class family in central Dublin. By the end of the 1970s, she became involved in a number of radical activities in London, where she came to study. When she qualified for community service in 1977, she was a single mother and was looking for part-time work. But she couldn't find anything and faced reality when she took on an unskilled job.

During the year, Boyle met regularly with a small group of women in the living room of her housing society to consider what could be done. Inspired by an organization called New Ways of Working in San Francisco, they formed the

a work-sharing project to advocate for the possibility of a formal division of staff positions between two people.

All of this unfolded in the crucible of the women's liberation movement of the 1970s, when women in the US and Europe pushed for fundamental reforms in relationships—intimate, professional, and political. Some unions and employers in the US and UK played with flexible work in the 1960s to allow professional women to remain in the paid labor force after having children. By the mid-1970s, a study by the European Economic Community found that flexible working hours were the only measure most likely to expand women's professional opportunities. Meanwhile, a new wave of massive public pressure on women's rights has swept across Europe and the United States. It was in this context that feminist activists first explicitly linked flexible working practices with the hope of a more equal society.

The 9 to 5 workweek worked well for most men, but was inherently at odds with caring for children.

The post-war expansion of higher education created a large group of women with vocational training and new aspirations for successful careers. By the 1970s, the rising cost of living and stagnating wages meant that the income of one male breadwinner was no longer enough to support an entire family, and more women began working to make ends meet. Between 1951 and 1971, the percentage of married women in the labor force increased from 22 percent to 42 percent. It only continued to grow in the 1980s and beyond. By 1989, among families with two parents, 57% had double income.

As women organized into activist groups, they reflected on the struggle to combine paid work with care work - what was called the "second shift". During the 1970s and 80s, feminists advocated the introduction of flexible working hours, telecommuting, and ideas such as "part-time work" and "work-sharing." They hoped that this new policy would increase equality of employment opportunity for women, change the gender division of labor at home, and challenge traditional views of paid work.

The program was both pragmatic and utopian. The idea was to open up a part-time job in a theoretically limitless range of occupations. The division of work will mean reduced working hours and a chance for mothers to continue paid work without losing benefits or status. At the same time, it would challenge the hegemony of what activists saw as the 9-to-5 40-hour work week, which suited most men well but was inherently antithetical to providing childcare.

Although the supporters of work-sharing were mostly college-educated white, middle-class women, they knew that work-sharing could not be a panacea for all workers, especially those in need of a full income. But this idea reflected the utopian belief that the division of labor would encode work, and by extension society, with an entirely new set of values. Part-time workers cannot be “selfish or possessive,” as Pam Walton, an urban planner and early part-time activist, put it — their responsibilities require teamwork and downplaying ego. The division of work favored what were traditionally considered "feminine" values, such as collaboration, listening, and sharing. It also promised to be what Boyle and Walton called "a more social way of working." Activists imagined that changing work culture would change work for everyone.

In addition to pushing for reform of the structure of paid work, feminists have advocated for kindergartens in the workplace. As the post-war British state cut support for childcare, a growing number of working mothers found themselves in a difficult position. Feminist groups such as the National Campaign for Child Care continued to demand government support for child care throughout the 1980s, but many activists have come to terms with the reality of more than minimal welfare. Instead, they started looking to employers for solutions. The same was true in the US, where a less comprehensive welfare state meant that activists were accustomed to turning to the private sector to apply for benefits.

Feminists pushed for kindergartens in a variety of workplaces, from universities to grocery stores. These campaigns have recognized that flexibility alone is not enough, especially for those who want or need to work full-time or earn low wages. In 1970, Pam Calder, lecturer in psychology at London's South Bank Polytechnic Institute, campaigned for workplace kindergarten. Even though it was eventually successful, it took five years to get started.

a job during which Calder struggled to provide reliable child care. On the day she was due to go to work, when her daughter was three months old, the registered babysitter she hired was nowhere to be found. In desperation, Calder left her with a kind neighbor. The arrangement continued, but this childcare solution was "not something to be relied upon as a system".

Whether advocates for employer-led or residential childcare, they were motivated by a common vision—the belief that childcare services should be accessible to all; should bring together different groups at the local level; and should not be provided by low-income women of color solely for the benefit of middle-class white women. This vision included the hope that childcare and early education would be anti-racist and anti-sexist in content.

Although they were first introduced for women, they eventually expanded to include workers of both sexes.

In practice, using child care as a means to promote equality has been challenging both in society and in the workplace, and white activists have not always recognized or removed the unique barriers for black families. As early as the mid-1980s, black childcare activists highlighted these tensions. In 1985, members of the National Child Care Campaign's black advocacy group expressed their opinion that "the NCCC is an organization for whites and doesn't seem to think about how other people raise children differently."

Despite the difficulties of creating a broad feminist movement, by the 1980s, feminist campaigns to remake jobs gained momentum, especially in the public sector. In both the US and the UK, employers ranging from school districts to local government councils have introduced job sharing policies. Although they were first introduced for women, they eventually expanded to include workers of both sexes. The London Borough of Camden led the way by introducing extended parental leave, a formal work-sharing scheme open to all employees regardless of gender or pay level, and an on-site children's centre. The Council has worked tirelessly, though not always successfully, to ensure that hours of operation meet the needs of its workers and that they can be used by employees of all income levels and backgrounds. It is these politicians

Up until the 1990s, workplace feminists presented flexibility in working hours and location as just two of a number of benefits needed to support workers as human beings with lives and responsibilities beyond those provided (and exhausted) capitalism. In 1999, Leeds Animation Workshop - a British feminist film collective - released the film Working with Care, which tells the fairy tale story of the queen and her staff. As a benevolent ruler, she guaranteed all royal staff not only flexibility in terms of hours and places of work, but also access to childcare and the elderly, a laundry company, a cafeteria, a gym, a massage center and a union office. The workplace was like a city centered on the needs of the community.

Apart from the progressive sectors of the public sector, the history of the development of Anglo-American recruitment practices was quite different. Public sector policies to meet the needs of caregivers were made possible by generous post-war economic growth. But in the 1980s, economic stagnation and a shrinking public sector meant that progressive innovation in the workplace largely faded away.

Now the private sector has taken over the baton of structural job reform. The largest American and British companies, from American Express and Rank Xerox to NatWest bank and Sainsbury's supermarket, have implemented the so-called "family" policy for the first time. In less than a decade, private companies have begun to actively compete with each other to be considered the best perks for workers with families. But what at first glance looked like a resounding victory for the feminists, in reality turned out to be a simplistic compromise.

The openness of the private sector to rethinking women's work was far from automatic. Rather, it depended on the relentless, concerted efforts of feminists seeking organizational change. In 1978, academic Margery Povall received funding from the German Marshall Fund of the United States for a project to stimulate affirmative action for women in Europe. She spent a year at NatWest in the UK. There, Povall tried to counter the suggestion that women always want to stay at home after having children, and stressed that the bank itself would benefit by keeping trained female employees.

udnikov. But she faced an uphill battle with company managers.

It took her a long time, Powall told me in an interview, to realize that "these men don't understand what a married business woman is." She often found the process tedious and depressing, but at the same time inspiring: "Interviews with managers turned me into a feminist." By 1981, Powall had convinced the bank to introduce one of the UK's first maternity leave refund schemes. But her further recommendations, including flexible scheduling, on-site child care and parental leave for men and women, did not yield much results.

Nevertheless, feminists have redoubled their efforts to engage with the private sector. As many activists struggled to stay afloat financially, there were benefits to working with the private sector as well. What started as explicitly leftist political activist groups, including the Job Sharing Project, have been transformed into politically neutral non-profit organizations. In 1980, the Job Sharing Project was named New Ways to Work, in parallel with the American organization that inspired it, and became an advisory body working with the private sector. In an attempt to stay connected to their political vision, feminist charities such as New Ways to Work sought to capitalize on the resilience and trust generated by the 1980s business consulting boom.

Activists have long suffered from a blind spot when it comes to the realities that low-income women face.

At the same time, private sector employers in the UK have become increasingly nervous about demographic shifts that will reduce the pool of traditional recruits. Politicians talked about the "demographic time bomb" that resulted from the sharp fall in the birth rate in the late 1970s, following the growing availability of contraceptives and the legalization of abortion. The fear was that by the mid-1990s this would lead to a sharp decline in the number of school graduates entering the labor market. As a consequence, the need to recruit and retain female staff has become urgent. Progressives have taken this opportunity to promote feminist ideas about restructuring paid work, but, most importantly, they have also internalized some of the private sector's own interests and ways of framing issues.

In collaboration with business, activists began to shift the focus from utopian ideas about the division of labor and the needs of mothers to the benefits of flexibility and the needs of workers in general. By formulating demands in terms of the needs of both men and women, activists could fight back against the simplification of the flexible work program. This allowed them to overcome many of the hurdles Powall faced a decade ago and form a new "business case" for flexibility. However, the activists walked a fine line between appealing to corporate profits and maintaining an overtly feminist agenda.

Companies soon discovered that flexibility, along with basic maternity leave and the ability to return to work after the baby was born, served their own financial interests. Greater flexibility in when and where white-collar workers performed their work had no measurable impact on staff productivity, quality, or efficiency. At the same time, flexible policies allowed companies to pose as "progressive" and thus appeal to an increasingly economically important group of professional women. Significantly, the same organizations that were enthusiastic about the introduction of flexible working hours nevertheless tended to refuse on-site childcare. Several companies have established staff day care centers since the late 1980s, but this has been the exception to the rule. It was overwhelmingly rejected as too expensive; instead, they followed the example of American Express and created childcare information services for parents. These included referring parents to resources, but otherwise shifting the responsibility to the families themselves.

However, many private sector companies have begun to spread triumphant tales of healthy, happy employees in attractive and comfortable environments. To some extent, feminist organizations contributed to this image. Beginning in 1990, the Working Mothers Association, a working parent charity, began holding Employer of the Year competitions to "encourage employers to adapt corporate culture to the needs of working parents." . These promotional events drew attention to organizational changes, but the vast majority of working families were left without any new benefits or forms of material support.

, even as the number of dual-income households continued to rise.

The rationale behind the corporate proponents of the new employment policy differed greatly from feminist visions of a more equal society. Therefore, it is not surprising that the private sector has been selective in its acceptance of feminist ideas and language. However, it wasn't that feminism was simply being eaten alive by the new corporate capitalist culture; rather, feminist activists and organizations actively worked in and through the private sector to shape what became the status quo. If the new policy wasn't everything activists had hoped for, introducing some flexibility seemed like a step in the right direction.

Over the past 40 years, flexibility has allowed some, primarily white, middle-class people to have more control over their work lives. This has had a transformative impact on professional women in particular. The need for parental leave and other forms of support for workers with family responsibilities is now well known in both the UK and the US, if not already in organizational practice.

But now that we're right in the 21st century, perhaps we're finally turning the corner and acknowledging that flexibility alone is not an adequate guarantee of well-being. First, the blindness of the original feminist flexible work campaigns to the needs of low-income workers and their families has become more blatant than ever. For shift workers who must work flexible hours in the service industry, what is most needed is a stable schedule, not more flexibility. As the 2020 pandemic has shown, working from home or with flexible hours is not always possible or even desirable. Women still bear the brunt of the burden of caregiving. A broader rethinking of work and its place in our lives is overdue.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, theorists and decision makers have tended to think about work-family tensions through the lens of "work-life balance". To Boyle, this concept seems very typical of the middle class and not particularly radical. As she told me from her boat, pointing to those lounging around in the Google offices, "They shouldn't work long hours and then be so exhausted that they can't go and do other things."

Moving forward may require a new language that is not centered on mothers or parents, or even family friendliness or work-life balance. Communities are united not by employment, but above all by bonds of care. The future of work must include an awareness of our collective responsibility for and to our children, as well as the elderly, the sick and other vulnerable but vital members of our society. Moreover, it must be a vision that embraces these responsibilities not only in terms of work, but also as encompassing a range of human values.